|

Travel Two Centuries Ago

by Tricia Noel

| |

|

| |

Yates County bus in the snow. |

| |

|

In modern times, when we can drive from Geneva to Penn Yan in twenty-five minutes, or fly from one country to another in a matter of hours, it is hard to imagine the sheer difficultly and danger involved in moving from place to place two centuries ago.

In a reminiscence published in the Penn Yan Democrat in 1908, a correspondent who signed himself simply “B,” recalled moving to Penn Yan from New York City in December 1838. “I was seven years old,” he wrote. “My mother, a young widow, freshly bereaved, my brother and sister, both younger than I, composed the party.” A trip that would today take six hours by car – from New York City to the Finger Lakes Region - took weeks on a combination of stagecoaches and canal boats. B’s widowed mother and her children ended up almost stranded near the northern end of Cayuga Lake when she did not have enough money to pay the family who ran the ferry, which she would have needed to take to avoid the marshes around Montezuma. The ferryman’s wife, taking pity on B’s mother, protested that if she paid them what was left, she would not have enough money left to make it on to Penn Yan. She told her to send it later, and sent them on to Geneva with a basket of food.

In Geneva, B’s mother engaged the help of Nelson Thompson to get them to Penn Yan. Again, her money was not quite enough to get them there, but Thompson didn’t mind. He packed the family into a sleigh “overflowing with buffalo robes. He planted Mother in a corner, and then took each of us in his arms and buried us beneath the robes which he tucked so tightly that there was only one little hole for us to peek through and another one to breathe through.” Then they proceeded to drive through a blizzard, the likes of which we never see anymore. B wrote, “…a whirlwind of snow which no words at my command can fittingly describe, was raging. The air was like an helpless ocean tossed and upheaved by winds piercingly cold, and so filled with snowflakes that our eyes were blurred and our nose tips frost-smarting, and the very current of our breath reversed. The roads were one succession of snowdrifts which, like billows, lifted us to heights which made us dizzy, and engulfed us in depths from which there seemed no resurrection…To Mother it was an ordeal which not only unstrung and demoralized her nerves, but almost paralyzed her with fright.” Thompson, who swore continuously during the hours-long drive from Geneva to Penn Yan, won the children over by giving them candy and by his resemblance to Santa Claus. He won B’s mother over, despite her fear, by not charging for the trip. The family moved in with two unmarried aunts, where the next day, Rhoda Ann Bradley brought over fresh ginger snaps and milk for the “children who came through the snowstorm.”

|

|

| Town of Seneca, Cromwell's Hill |

|

| |

|

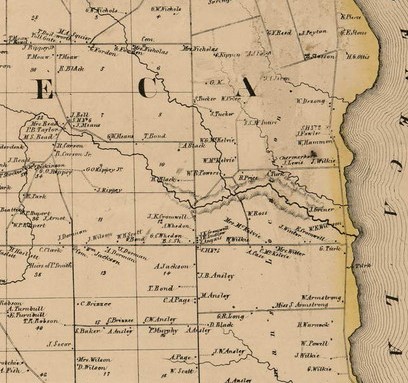

That same route, from Geneva to Penn Yan on the Pre-Emption Road, caused much trepidation and complaining a decade before, for a section of the road that goes unnoticed by drivers today. In the June 27, 1826, edition of the Yates Republican, the editor complained about Cromwell’s Hill, “situated about halfway between Geneva and Bellona.” This road, on this hill, which he called “formidable, narrow and dangerous,” he moaned, made the otherwise safe trip between the two communities fraught with hazard. “Carriages have been upset, lives endangered, and bones broken in descending and ascending this steep, crooked and narrow defile,” he wrote. Although nowhere on Pre-Emption Road meets this description today, the tiny crossroads community of Cromwell’s Hollow, sometimes called Billsboro, is likely where he is referencing. A small collection of houses near the Pre-Emption and Billsboro intersection, Cromwell’s Hollow sits just south of a dip in the road that crosses Wilson Creek near the western end of Snell Road. The hill that creates this valley, although barely noticeable today, was graded over the years to make it less hazardous to travelers. The editor did finish his article by stating with satisfaction that work was being done to make it more level.

Another problem facing travelers two centuries ago was the near-blind pitch blackness and the close vicinity of wild animals. Wolves being nocturnal, they plagued people who were forced to travel at night. Joseph Jones, a Quaker surveyor who came to Yates County in the 1790s, found himself stalked by wolves with his partner, Jesse Davis, in 1791. One night Davis and Jones found themselves surrounded by wolf howls, only to hear panther screams in the distance. They were forced to carry burning torches to keep the animals at bay. Lois Pattison Spencer, who moved to the area near Kashong in 1788, recalled riding her horse many times to visit another family, and on the way back, as darkness fell, the howl of wolves came from both sides of her path. Alexander Porter of Italy Hollow once took his grain to the Friend’s Mill on the Keuka Outlet, west of Penn Yan. En route home, wolves surrounded him. Sadly, his horse became exhausted, and he was forced to leave it behind to the wolves and run to the nearest home. In 1801, Jacob Arnold was nearly killed near Sherman’s Hollow Road when surrounded by a pack one night; neighbors hearing his shouts arrived to scare off the pack. And one young couple wrote that when going out to attend church revivals at night, wolf and panther sounds accompanied them the entire way.

The next time you are driving along Yates County’s roads, try to imagine the primitive conditions of the past. Even the oldest of cars would be preferable to a carriage trying to scale a hill or being followed by wild animals.

|